The allure of marble has captivated human civilization for millennia. Its cool, veined surfaces have adorned palaces, temples, and grand estates, symbolizing luxury, permanence, and an undeniable connection to the earth’s artistry. Yet, the very qualities that make natural marble so desirable – its uniqueness, its beauty, its sheer elegance – also contribute to its significant cost and often, its practical limitations. This is where the world of artificial, or engineered, stone enters the picture, offering a compelling alternative that has rapidly gained traction in modern design and construction. From sleek kitchen countertops to sophisticated bathroom vanities and striking wall claddings, artificial marble has become a ubiquitous presence in our living spaces. But as we embrace its aesthetic appeal and functional advantages, a nagging question often surfaces, a whisper in the back of our minds: does this manufactured marvel harbor any hidden health concerns? Specifically, the specter of formaldehyde often arises in discussions about composite materials, and artificial marble is no exception.

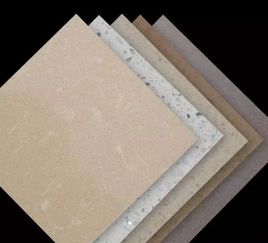

To truly understand the question of formaldehyde in artificial marble, we must first delve into what this material actually is. Unlike its natural counterpart, which is quarried directly from the earth, artificial marble is a man-made product. Its creation typically involves a complex process of combining natural stone aggregates – such as quartz or marble chips – with resins, pigments, and other additives. The precise composition can vary significantly between manufacturers and product lines. However, the binding agent, the substance that holds these particles together and gives the finished product its solidity and form, is often a polymer resin. These resins are typically thermosetting plastics, meaning they undergo a chemical reaction when heated and cured, forming a rigid, durable structure. Common resins used in the manufacturing of engineered stone include polyester resins and epoxy resins.

Now, let’s bring formaldehyde into the conversation. Formaldehyde (CH₂O) is a simple organic compound that is a colorless gas with a pungent odor. It is a ubiquitous chemical, found naturally in small amounts in the environment, and is also a byproduct of various biological processes. However, it is also widely used in industry, particularly in the production of resins and adhesives, and as a preservative. Its role in the creation of engineered stone is primarily linked to the resins used as binders. Many synthetic resins, especially those based on urea-formaldehyde (UF) and melamine-formaldehyde (MF), are known to release formaldehyde over time. This release, known as off-gassing, can contribute to indoor air pollution, as formaldehyde is classified as a volatile organic compound (VOC). VOCs are chemicals that can vaporize easily at room temperature and can have adverse effects on human health, ranging from respiratory irritation and headaches to more serious long-term health problems.

So, the critical question becomes: do the resins used in artificial marble necessarily contain or release formaldehyde? The answer, like many things in the world of materials science, is nuanced. Not all resins are formaldehyde-based. While urea-formaldehyde and melamine-formaldehyde resins are common in certain wood composite products like particleboard and MDF, the resins employed in high-quality engineered stone are often different. Manufacturers of premium artificial marble often opt for unsaturated polyester resins or epoxy resins, which, when properly formulated and cured, have a significantly lower potential for formaldehyde off-gassing. The curing process itself is crucial. During curing, the resin undergoes polymerization, transforming from a liquid or semi-solid state into a hard, stable matrix. A complete and thorough curing process is essential to minimize the presence of unreacted monomers, including any potential formaldehyde precursors, within the final product.

Furthermore, the sheer proportion of resin to stone aggregate plays a role. In many high-quality engineered stones, the aggregate content can be as high as 90-95%, with the resin acting as the binder. This high proportion of mineral content means that the amount of resin, and therefore any potential formaldehyde associated with it, is relatively low compared to other composite materials where resin forms a larger part of the overall structure. The manufacturing processes themselves have also evolved. Manufacturers are increasingly aware of the importance of indoor air quality and are investing in technologies and formulations designed to reduce or eliminate VOC emissions, including formaldehyde, from their products. This includes stringent quality control measures during production and the use of advanced curing techniques.

However, it’s not a simple black and white picture. The term “artificial marble” is broad, encompassing a wide range of products with varying compositions and manufacturing standards. Lower-quality or cheaper alternatives might indeed utilize resins with a higher propensity for formaldehyde release. The presence of fillers or additives, while not always the primary source, could also contribute to the overall VOC profile of the material. Therefore, while many modern, reputable artificial marble products are designed to be low in formaldehyde emissions, it is not an inherent guarantee across the entire market. This is where consumer awareness and informed choices become paramount. Understanding the basics of what constitutes artificial marble and the potential sources of formaldehyde allows consumers to ask the right questions and seek out products that prioritize health and safety.

The journey from raw materials to the polished slab of artificial marble adorning your kitchen is a testament to modern material science and manufacturing prowess. As we’ve touched upon, the core components are typically natural mineral aggregates – predominantly quartz, but sometimes marble chips or other minerals – bound together by a polymer resin. The magic, and sometimes the concern, lies in this resinous matrix. While the mineral component is inert and poses no direct risk of formaldehyde emission, the resin is where the potential for concern originates. The key differentiator between a product that is a concern and one that is not often boils down to the type of resin used and the rigor of the manufacturing process.

Unsaturated polyester resins are a popular choice for many artificial marble manufacturers. These resins, when properly formulated and cured, are known for their excellent mechanical properties, durability, and resistance to chemicals and stains. Crucially, they generally have a very low potential for formaldehyde off-gassing. This is because the “formaldehyde” component in their name refers to the chemical structure of the unsaturated polyester molecule itself, not necessarily that free formaldehyde is being released from the cured product. Think of it like this: the building blocks are arranged in a way that doesn’t readily break down to release formaldehyde gas. The curing process, a chemical reaction that hardens the resin, is critical in ensuring that any residual unreacted monomers are minimized, further reducing the possibility of off-gassing.

Epoxy resins are another category of binders used in some engineered stone products. Epoxy resins are also thermosetting polymers known for their exceptional strength, adhesion, and chemical resistance. They are often used in high-performance applications. Like unsaturated polyesters, properly cured epoxy resins typically exhibit very low formaldehyde emissions. The focus here is again on the quality of the resin, the formulation, and the thoroughness of the curing process.

The real question mark arises when less expensive or older formulations of resins are employed, or when the manufacturing process is not meticulously controlled. Some composite materials, particularly those designed for lower-cost applications or those that have been manufactured for many years, might have utilized urea-formaldehyde (UF) or melamine-formaldehyde (MF) resins. These resins are incredibly effective and economical for binding wood fibers in products like particleboard and medium-density fiberboard (MDF). However, they are also known to be sources of formaldehyde off-gassing. The chemical bonds within UF and MF resins can break down over time, releasing free formaldehyde into the air. If these types of resins were to be used in artificial marble, or if there were significant residual formaldehyde in the uncured resin that wasn’t effectively trapped during curing, then the material could contribute to indoor air pollution.

The good news for consumers is that the market has, for the most part, shifted towards safer alternatives, especially for applications where indoor air quality is a primary concern, such as kitchen and bathroom surfaces. Leading manufacturers of artificial marble and engineered stone are acutely aware of the health implications of VOCs. Many have invested heavily in research and development to create proprietary resin formulations that are specifically designed to minimize or eliminate formaldehyde emissions. They often use the term “low-VOC” or “VOC-free” to describe their products, and some have sought third-party certifications to validate these claims.

These certifications can be invaluable for consumers. Organizations like Greenguard, NSF International, and various national building standards bodies have developed rigorous testing protocols to assess the emissions from building materials. Products that achieve certifications from these bodies have undergone independent testing and have demonstrated compliance with strict limits on VOC emissions, including formaldehyde. When you see a certification logo on an artificial marble product, it signifies a commitment by the manufacturer to producing a healthier material.

Beyond certifications, transparency from manufacturers is key. Reputable brands are often willing to provide detailed product specifications, including information about the resins used and their VOC emission data. Some may even provide Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), which offer a comprehensive lifecycle assessment of a product’s environmental impact, including its emissions. Armed with this information, consumers can make informed decisions based on their specific needs and concerns.

It’s also worth considering the context of where the artificial marble is used. While formaldehyde off-gassing from countertops might be a concern, the overall contribution to indoor air quality depends on the quantity of material used, the ventilation in the space, and the presence of other potential VOC sources. However, given that kitchens and bathrooms are often high-traffic areas within homes, and surfaces like countertops are in close proximity to occupants, choosing materials with low or no formaldehyde emissions is a prudent choice for creating a healthier living environment. The evolution of artificial marble manufacturing has, for the most part, addressed these concerns, but diligence and informed selection remain the consumer’s best tools in navigating the world of modern building materials. The beauty and functionality of artificial marble can indeed be enjoyed with the peace of mind that comes from a healthier home.